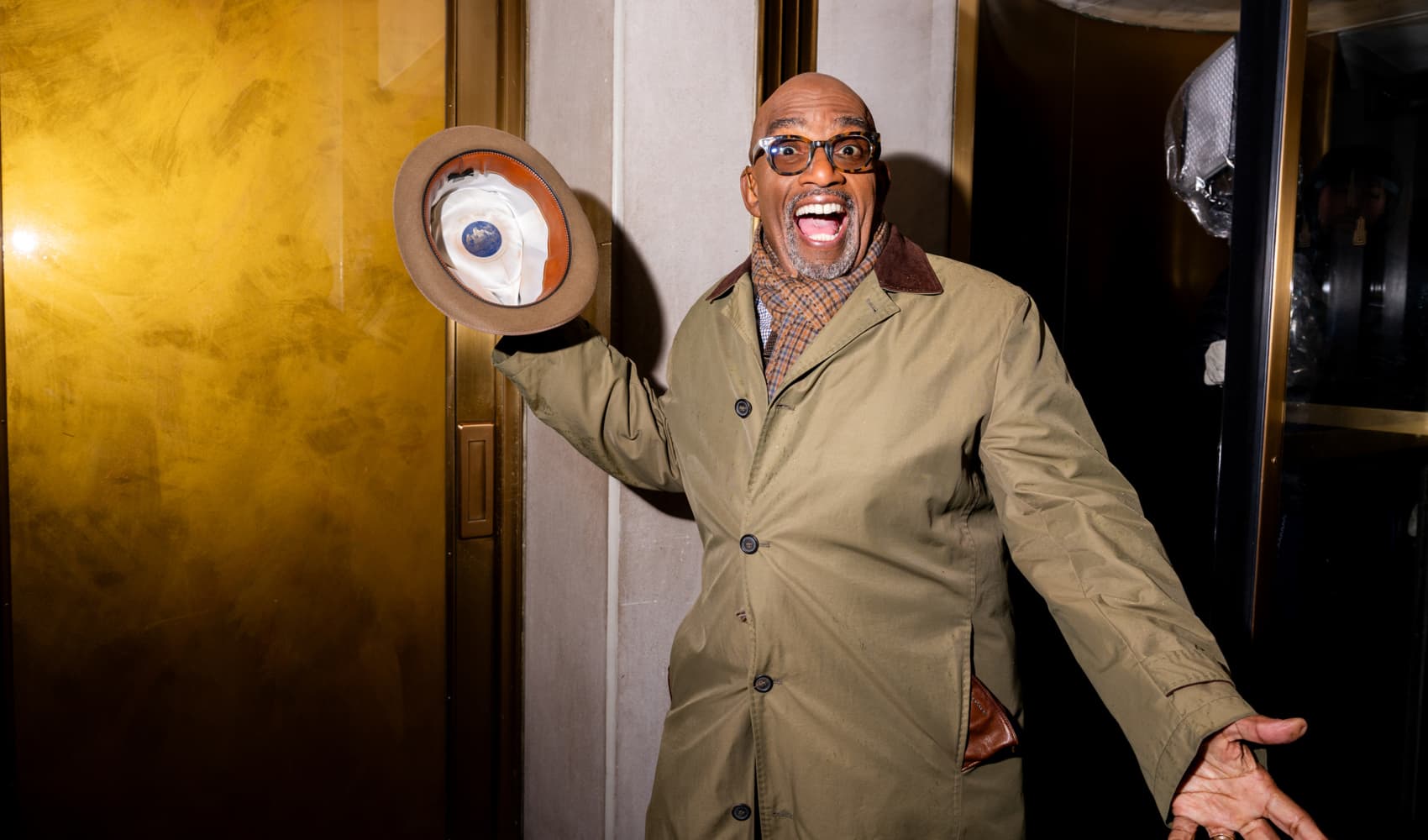

Dave Bolotsky, founder and CEO of Brooklyn-based Uncommon Goods, offers a coveted family leave benefit for employees.

Dave Bolotsky didn't want a career on Wall Street.

Still, as a 22-year-old trying to move out of his parents' home and pay off his student loans, he took an analyst job at investment bank First Boston in 1985. By 1999, he had worked his way up to a managing director position at Goldman Sachs, where he says he was due to receive about $10 million worth of stock when the bank went public.

He turned down that major bonus to pursue his own business idea instead: Uncommon Goods, an online, small-production gift store. The website offers a variety of products made by independent artists and designers, such as function-forward items like a popcorn bowl that separates out the unpopped kernels.

Bolotsky had the idea after visiting a craft show and seeing the desire shoppers have for personalized, handcrafted items.

Get top local stories in Connecticut delivered to you every morning. Sign up for NBC Connecticut's News Headlines newsletter.

"If I'm buying [you] a birthday gift, I want you to know that I went the extra mile, that I put some thought into it, and I know what makes you tick," he tells CNBC Make It. "You're not going to get that at Pottery Barn or some random store at the mall."

Many people today would — and did, back then — balk at the idea of Bolotsky walking away from a $10 million payout. But, "my attitude was, I'm 36 years old, I don't want to live a life of regret, and money is not what makes me happy," Bolotsky says.

Now, 25 years later, he still doesn't regret that decision.

Money Report

Leaving Goldman Sachs 'seemed a little bit crazy'

"The idea of walking away just as Goldman's going public, seemed a little bit crazy," Bolotsky says. "My department gave me a going away present that had a baby picture of me and they gave me a huge jar of nuts [with it], and it said, 'David's nuts.'"

His peers asked Bolotsky why he didn't just wait a year or two, collect his stock bonus, then leave Goldman Sachs with a hefty "nut" to start his new venture.

"I felt that so much was changing, and so much was happening [with] the internet at that time, and it was still early days that there really was an opportunity," he says.

Not only was it a risk to leave a multimillion-dollar bonus and a steady paycheck, but online shopping wasn't ubiquitous yet. Starting an ecommerce business was no sure thing.

"While it was scary for me to leave [Goldman], I've always lived pretty conservatively from a financial perspective," Bolotsky says. He lived frugally and had been saving much of his Wall Street earnings, so "it was not nearly as big a risk as somebody who mortgages their home or takes on a lot of debt. I didn't have to do that."

Uncommon Goods' early investors were "friends and family," he says, including retailers he'd gotten to know from his time as an analyst on Wall Street.

The path to profitability

Despite early sales success, it took a few years for Uncommon Goods to really get off the ground. Bolotsky was "loaning the business much of my life savings" for the first few years to make it to the lucrative winter holiday season. Bolotsky didn't take home a salary until 2005, living primarily off his savings in the meantime.

The company started with hefty overhead costs that would have required rapid and exponential sales growth to recoup, Bolotsky says. Instead, it reduced operating costs dramatically by shrinking the team from 35 employees to five and downsizing the production space while growing sales at a realistic pace. Uncommon Goods had its first profitable year in 2003 — four years after its inception.

Since then, the company has remained profitable every year except 2022, when sales settled down from a pandemic boost, but operating costs grew and remained elevated.

Profitability remains a priority for Bolotsky, but not if it were to mean compromising the company's core values. In 2007, Uncommon Goods became one of the first ever B corporations, a designation that shows a company is committed to promoting a positive social and environmental impact.

Balancing those values — and the cost of doing so — with growing profitability is an ongoing challenge, but an important one for Bolotsky. Uncommon Goods' warehouse staff in Brooklyn, New York, earns a minimum of $20 an hour, for example. That's $4 above the minimum wage in the city and nearly triple the federal minimum wage of $7.25.

"When business is great, it's easy to balance both [core values and profitability]," Bolotsky says. "When business isn't great, you have to make tough choices."

'Very happy with the path I've taken'

Uncommon Goods has continued to grow, counting 144 year-round employees as of 2025 and receiving over a million orders per year for the last five years.

Bolotsky knows he may have wound up richer today had he taken the stock grant and continued working in investment banking, but "I am very happy with the path I've taken," he says. It's been challenging running a business and even "lonely at times," he says, but "rewarding."

Collaborating with his employees and building a business that has an impact on a wide network of people, from the warehouse to customers at home, is "so much more satisfying to me compared with a role where I was more of a critic," Bolotsky says.

Want to up your AI skills and be more productive? Take CNBC's new online course How to Use AI to Be More Successful at Work. Expert instructors will teach you how to get started, practical uses, tips for effective prompt-writing, and mistakes to avoid. Sign up now and use coupon code EARLYBIRD for an introductory discount of 30% off $67 (+ taxes and fees) through February 11, 2025.

Plus, sign up for CNBC Make It's newsletter to get tips and tricks for success at work, with money and in life.