Connecticut’s Chief Medical Examiner Dr. James Gill is not often in the public spotlight. Gill admits he prefers to keep a low profile. However, after this incredibly difficult year, Gill has chosen to speak out in an exclusive interview with NBC Connecticut’s Dan Corcoran.

Gill’s team of about 50 full-time staffers at the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner (OCME) has been working non-stop since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. The work of certifying cause of death over the last year has been grueling, at times overwhelming, but also extremely gratifying, Gill said.

By March of 2021, there were approximately 8,000 COVID-related deaths reported since the pandemic began.

“The thing that goes through my mind is the families, a lot of the time, they weren’t able to be with their family, with their next of kin when that person was dying because of the limitations, because of the infection,” Gill said. “I think that compounded the loss even more that there was this distance that they couldn’t really manage.”

Get top local stories in Connecticut delivered to you every morning. >Sign up for NBC Connecticut's News Headlines newsletter.

“Obviously, the number of deaths was unimaginable; the number that we’re going to see,” Dr. Gill said.

Obviously, the number of deaths was unimaginable; the number that we’re going to see.

Dr. James Gill

In a typical year in Connecticut, there are about 2,500 deaths, on average per month, Gill said. But in April of 2020, the state saw about 2,500 additional deaths from COVID, essentially doubling the number of deaths in that single month compared to what would normally occur.

“You can imagine the effects on families, on funeral homes even, on managing all that, on hospitals,” Gill said. “It was a tremendously difficult month.”

For Dr. Gill and his staff, keeping up with the sheer number of deaths that needed to be investigated was extremely difficult.

“We had kind of do a lot of things on the fly,” Gill said. “We’ve had about the same number of full-time staff for the past four years. We really couldn’t increase our numbers. We changed some things in our computers so that we could easily track some of these deaths. We developed things with the hospitals so we could report them more easily by faxing some information to us instead of having to call it in, so that helped with our phone triage.”

Gill said the roles of certain staffers were adapted to help accommodate the increases in cases.

“We had to shift some of our investigative staff to handle the phones,” said Gill.

The number of deaths that were reported to the OCME increased about 30% in 2020, Gill said. Each of those deaths needed to be entered into the computer system and investigated, if the cause of death was still undetermined.

One of main objectives of Gill’s team was to determine if a death would be classified as "COVID-related."

The number of deaths that were reported to the OCME increased about 30% in 2020.

“For COVID-19 to be on the death certificate, it’s needs either have caused death or contributed to death in some way.”

For example, Gill said, the OCME investigated a death that was a homicide where the person survived for a day in the hospital. That person tested positive for COVID19, but COVID-19 was not indicated on his death certificate because he died from injury, Gill said.

“A lot of our investigation was reviewing the death certificates, making sure they were properly filled out, and that COVID actually played a role in their death,” said Dr. Gill.

“We did many autopsies on COVID deaths here,” Gill said. “The swab is obviously an important part of it, but we also would have instances where maybe it’s a suspected drug intoxication death versus a COVID death. In those instances, we need to do the autopsy to help try and distinguish the two and one of the things we look for is in the lungs; and you have a special type of reaction in the lungs, a special type of inflammation that you see with a COVID infection as opposed to other types of deaths. That would be the main reason why we would end up doing the autopsy as well as excluding the other causes of death with the autopsy.”

“The lungs become very, very heavy,” Gill said of what his team often observes in the lungs of a person believed to have died from COVID-19. “They’re filled with fluid and protein and sometimes you’ll see a superimposed infection, a typical bronchial pneumonia, that you typically hear of.

“Sometimes you may see some clots, blood clots, in the lungs as well. So it has a special microscopic pattern that we can see and it tells us that this is COVID tested,” he added.

“It is a kind of pathologic, clinical investigation and so, as I said with homicide, it’s just not that the person had a positive COVID swab, you need to look at the whole picture and make sure that it all fits,” Gill said.

“Often times, you’ll have a contributing condition such as maybe lung cancer or pulmonary emphysema or diabetes or obesity as what we call a ‘Part 2’ or contributing factor, whereas the main cause of death is the COVID infection, but why did that particular person die of a COVID infection while many other people survive it?,” Gill said. “We look at those other contributing factors and we found that people with high blood pressure, diabetes, obesity, they’re at greater risk of having a poor outcome with a COVID infection.”

“From a public health point of view, it’s important to list those contributing factors on the death certificate so that we can – looking at the big picture – why did this person die of COVID and another person may not have?" said Dr. Gill.

“Now, were at a point where everyone is getting swabbed all the time; every hospital admission, every nursing home, so that’s not really become an issue. But in the beginning, it was a little more of a challenge to identify those deaths because the swabbing wasn’t as easy to obtain,” said Gill.

We had about 9,500 deaths reported to us as ‘suspected’ COVID deaths and we went through 1,500 or more of them and found that some of them weren’t

Dr. James Gill

“We had about 9,500 deaths reported to us as ‘suspected’ COVID deaths and we went through 1,500 or more of them and found that some of them weren’t,” said Gill. “The thing that I am proud of is that we were able to accurately able to identify and certify these deaths, doing it in a timely manner to allow families to get on with their funeral arrangements and so forth.”

Recently, Dr. Gill briefed state lawmakers about operations at the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner. Much of the discussion focused on what Gill believes is an inadequate level of staffing.

“We have about 50 fulltime staff and that’s been the same it’s been for about four years, even those these increases,” Gill said. “We are trying to increase our working staff. The other challenge is our facility.”

Gill said the 32 year old OCME facility in Farmington was constructed when about 1,200 autopsies were conducted each year. Currently, Gill said, the office conducts nearly 3,000 autopsies per year. Gill said the facility needs to be expanded or replaced soon.

“We’ve already expanded some things for storage of bodies but we’re always right on the brink of storage, too,” he said. “That’s something we’re also addressing and seeing if we can get that done in the next year or two.”

Over the last year, Gill said his office received tens of thousands of dollars from the federal CARES act and from FEMA, but more was needed.

“I think some of the challenge is there’s not always dedicated money to medical examiners or coroners so we’re kind of limited in what we can actually get reimbursed for,” he said.

Gill said it was unclear if his office would be receiving additional funding through the recent passage of the American Rescue Plan, but he was hopeful that some money would be dedicated soon.

“These are challenges for anyone,” Gill said reflecting the past year. “I did work in New York City during 9/11, so I saw something similar, but this was even larger than that. Fortunately, this was more spread out, so the deaths didn’t come all at once.”

“March, April, May was pretty tough and then we had kind of a break during the summer and then obviously it picked up again; the second peak. But the second peak wasn’t as high as that first peak. It was more flattened. I think we were able to manage that better,” said. Gill.

“You have to remember that there’s always a family behind it and any delay is going to affect the family,” Gill said of the importance of his work. “We want to make sure that we get the autopsy done, get the death certificate approved and through so they can get on with their funeral arrangements. Otherwise, they’re going to have to wait days or longer and that’s always in the back of our mind.”

You have to remember that there’s always a family behind it and any delay is going to affect the family

Dr. James Gill

“I think medical examiners are kind of one of the more unrecognized but very important part of the public health system and the bereavement system for families,” Gill said. “When a person dies at a hospital, the family will meet with the physician usually and that’s kind of it. But there are questions that linger, and we can help answer those questions for the family.”

Gill said the continuous onslaught of deaths being reported and having to be investigated by his office was, at times, overwhelming.

“It’s something that was just constant,” Gill said. “Day in and day out, it was looking at the numbers, tracking them, looking at the deaths, following up on those; sometimes calling the physician or calling the family.”

“One of the current challenges with the COVID deaths are the delayed COVID deaths now. So, someone may have had COVID, they were in the hospital, they were discharged, now they’re in a nursing home and they die maybe weeks or months later,” Gill said. “How do we relate that to a COVID infection or not? Because some of those people have other health conditions and may have died without the COVID.”

Gill said those "delayed" COVID deaths are particularly challenging because his office must still determine if the death was, in fact, linked to the virus.

As for how his team of dedicated staffers persevered during this last year, Gill said they often leaned on one another.

“You kind of support each other and you focus on what needs to be done and you try to remember that we’re doing this for a family and really everyone pitches in,” said Dr. Gill. “We all kind of do it together.”

One area of work that Gill said he and his team were most proud of was their testing for COVID-19 at Connecticut funeral homes.

“There were some deaths that came to us reported as ‘suspected’ COVID deaths or deaths that didn’t even have COVID on the death certificate, Gill said. “But we went to the funeral homes and did the swabbing at the funeral homes and we were able to diagnose or confirm the diagnosis of COVID.”

Gill said his profession is not one that many people associate with helping those who are alive.

“People always think ‘oh, you just work with the dead’, but we really are always thinking ‘how can our work help the living?’,” Gill said. “By making those diagnoses in the funeral home, we were helping the living by answering their questions and maybe even giving them important health information.”

People always think ‘oh, you just work with the dead’, but we really are always thinking ‘how can our work help the living?

Dr. James Gill

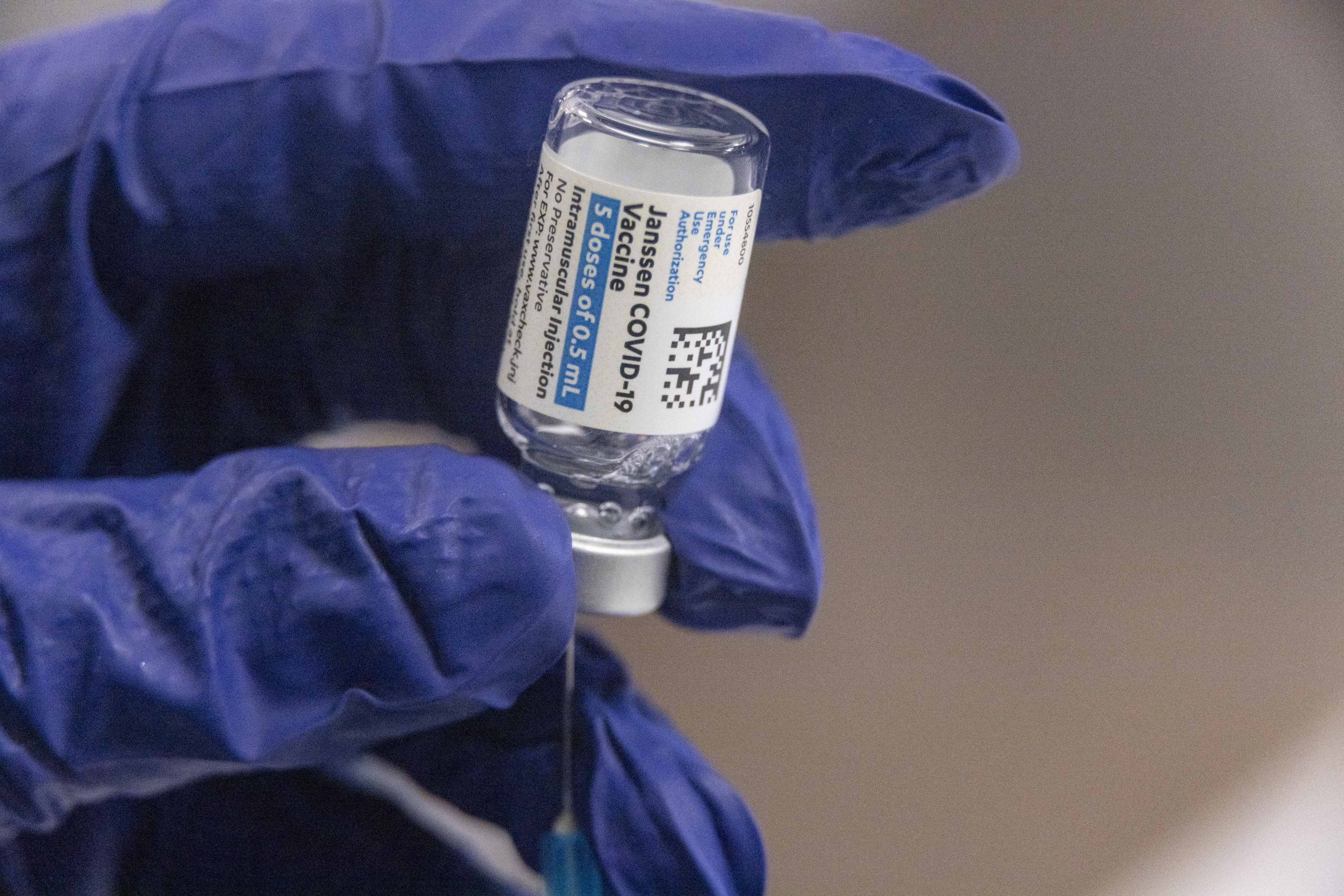

Seeing more and more COVID-19 vaccines go into arms in Connecticut and around the country, Dr. Gill is filled with hope.

“I see a lot of hope and optimism,” Gill said. “Every day, I look at those numbers; the hospital admissions, seeing their coming down, the deaths that are reported to us are coming down. I think we are all optimistic that we are getting past this.”

Gill, who admits he prefers to keep a low profile and often avoids media interviews, said he felt compelled to publicly thank his team for all of their hard work, specifically during the pandemic.

“I really wanted to thank the people I work with,” Gill said. They did this.”