Plans are still moving ahead to consolidate Connecticut’s 12 community colleges into a single accredited school by 2023, despite escalating resistance from faculty unions who question whether the complicated proposed merger will work or even makes sense.

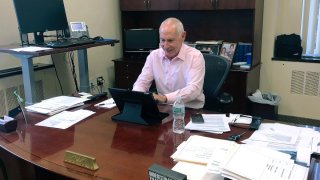

Connecticut State Colleges and Universities President Mark Ojakian said he’s optimistic that a regional accreditation organization will embrace a progress report that’s due in late April. It will update how Connecticut’s current system of independently operated and accredited state-run community colleges — with individual presidents, curricula and administrations — will be consolidated into one accredited school with 12 campuses and three regional presidents.

“I’m very hopeful that this is going to be a great year to move this forward,” Ojakian said in an interview last week with The Associated Press.

The consolidation concept was originally proposed in 2017 as a way to financially help a system serving 55,000 students that faced a $100 million budget deficit.

“Rather than go down a path of looking at reducing the number of institutions, I chose to go down this path, which would keep all of the locations open, including the satellites,” Ojakian said. He added the plan also calls for fewer administration and management positions and more “student-facing services,” such as advisers and faculty to help improve student success, including graduation rates.

CSCU’s latest submission will come two years after the accreditation body, now called the New England Commission on Higher Education, sent Ojakian and his staff back to the drawing board, suggesting a different approach. The group argued it was unrealistic to have a single statewide community college in place by July 2019. The commission’s chairman said in 2018 that the potential for “a disorderly environment for students” under the consolidation proposal was too high.

Today, that argument and others are being made by unionized faculty, who contend there are still many unanswered questions.

Local

“They’re a total mess. They’ve addressed no concerns,” said Lois Aime, director of educational technology at Norwalk Community College and a delegate to the Congress of Connecticut Community Colleges union or 4Cs. “They’re just moving forward. I don’t even know at this point why they’re moving forward and what it is they think they’re going to gain.”

Last month, for the first time, faculty and professional unions in the Connecticut State Colleges & Universities system issued a “statement of unity,” expressing their opposition to the latest version of the proposed consolidation, known as Students First. The five unions, which include members who work at the community colleges and other institutions, argued the plan “will not realize the projected savings, will be disruptive for students, will have negative consequences on critical student outcomes, and will erode the value of the community colleges for students and for the state of Connecticut for years to come.”

At last month’s meeting of the Board of Regents for Higher Education, a faculty advisory committee member read off a laundry list of outstanding questions, such as whether students’ access to federal financial aid could be at risk and what will happen to programs with similar content at different community colleges.

Aime contends lingering, unanswered questions, coupled with an unwillingness to listen to faculty, has expanded opposition to Students First. She noted close to 1,500 people signed a petition last year opposing the consolidation plan, including faculty, staff, students, retired community college presidents and former board of trustees members.

But Ojakian said many of the concerns that have been raised stem from “misinformation that’s been refuted time and time again.”

He contends there is quiet support for Students First. He noted how many faculty have been working on committees to hammer out the details of the plan, such as basic requirements for majors that could ultimately make it easier for students to take classes at different campuses.

“I think if you did a secret ballot on campuses, I think we would win,” he said. “But it’s not about winning or losing. It’s about making sure that we have a system in place into the future where students can succeed, where the equity gap is closed and where the finances are in a place that allows us to continue to operate well into the future.”