Convicted Mosque Shooter Embraces Islam

Ted Hakey Jr. now spends his days working to spread the word of the Muslim community in Meriden.

It's a far cry from what he felt in his heart two years ago when he was arrested after shooting at an empty mosque.

"I was a Muslim hater," Hakey told NBC Connecticut's Keisha Grant in an exclusive interview.

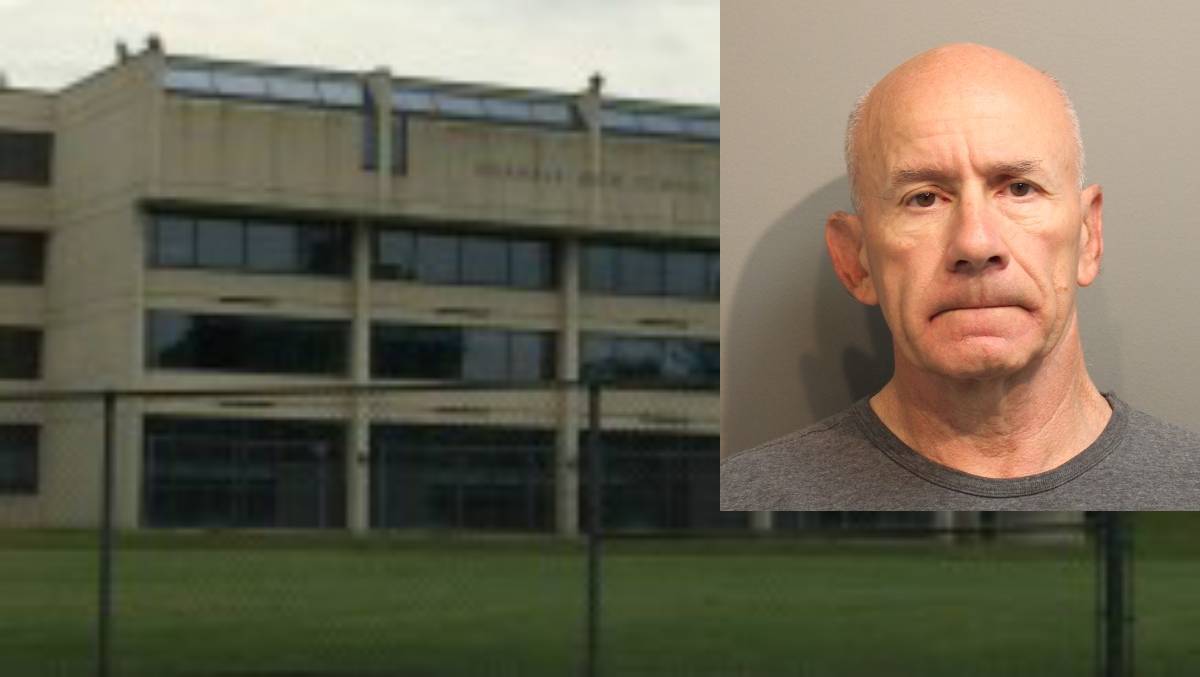

The former U.S. Marine was arrested for a hate crime in November 2015 after firing 30 shots into the Ahmadiyya Baitul Aman Mosque on Main Street with a high-powered rifle a day after the Paris attacks.

Hakey said he found himself intoxicated and fed up with attacks halfway around the world.

"The night of the Paris attacks, you could see the mosque clearly from my house because there were no leaves on the trees," Hakey said. "I went to get out of my car and looked over and kind of thought, 'Well, let me do something about it.'"

Four of the 30 shots Hakey fired tore through the Baitul Aman Mosque in the middle of the night. It took federal and local authorities just hours to trace the bullets back to Hakey and the FBI arrested him on federal hate crime charges.

Local

Zahir Mannan, one of the leaders of the mosque, said those bullets didn't just pierce walls. They also shot fear through the heart of the Ahmadiyya community. This sect of Islam is made up by the only group of Muslims who share one particular belief.

"That belief in itself, believing that Mirza Ghulam Ahmad was the Messiah, has made us the subject of persecution all over the world, but not here in America," Mannan said.

Hakey said his former understanding of Islam came from what he read online. He said Twitter, Facebook and other social media platforms not only led to his hatred of Islam but also fueled it.

"What you see on social media sites," Hakey said. "That was my education of Islam."

Hakey's life would change forever when he requested to sit down with the mosque leaders to apologize before his sentencing.

"This huge bodybuilder-type guy comes in and to see tears coming down his face and red cheeks, it humbled us as well," Mannan said. "It was a genuine connection that you can't fabricate."

Hakey said the conversation changed his attitude.

"If they handed this in any other way," he said, "I would've went to prison angry. I would've came out and I would've been just as angry."

Hakey said it wasn't just the words of the mosque leaders, but also their actions, that made him come around. While Hakey spent six months in prison, Mannan kept his promise to visit every other week.

Mannan also gifted Hakey with precious keepsakes, including his grandfather's Holy Quran.

"We talk about things I don't even discuss with some of my best friends," Hakey told NBC Connecticut. "It just became a relationship that's really, very tight."

Mannan called Hakey a "brother."

"He became my brother when he prayed next to me," Mannan said. "He prayed with me and he didn't have to do that."

Hakey considers himself a changed man. He hasn't converted to Islam, but he does spend his time spreading the word. He hopes his story inspires others to embrace the community that taught him the true meaning of forgiveness.

"I feel that I owe them just to get out there so that people don't make the same mistake that I did," Hakey said.

The Ahmadiyya Baitul Aman Mosque in Meriden invites the public inside every Friday night for a gathering called Coffee, Cake and Conversation.

"Knock on the door. You're always welcome," Hakey said. "There's no members-only thing in there, no secret handshake. You don't need a card. Everybody's welcome."

Hakey has been instrumental in bringing a whole new demographic for those conversation groups at the mosque.

Last year, Hakey spoke at Jalsa Salana, which is the oldest and largest Muslim convention in the country.

"I feel I owe them," Hakey said. "For the forgiveness I was given."