Measles vaccination rates for young children may be far lower than publicly reported, a troubling development that could mean the United States is closer than expected to losing its “elimination status” for the extremely contagious disease.

“We are experiencing an extremely concerning decline in measles vaccination in the very group most vulnerable to the disease,” said Benjamin Rader, a computational epidemiologist at Boston Children’s Hospital, an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School and the author of a recent study that looked at children’s vaccination rates.

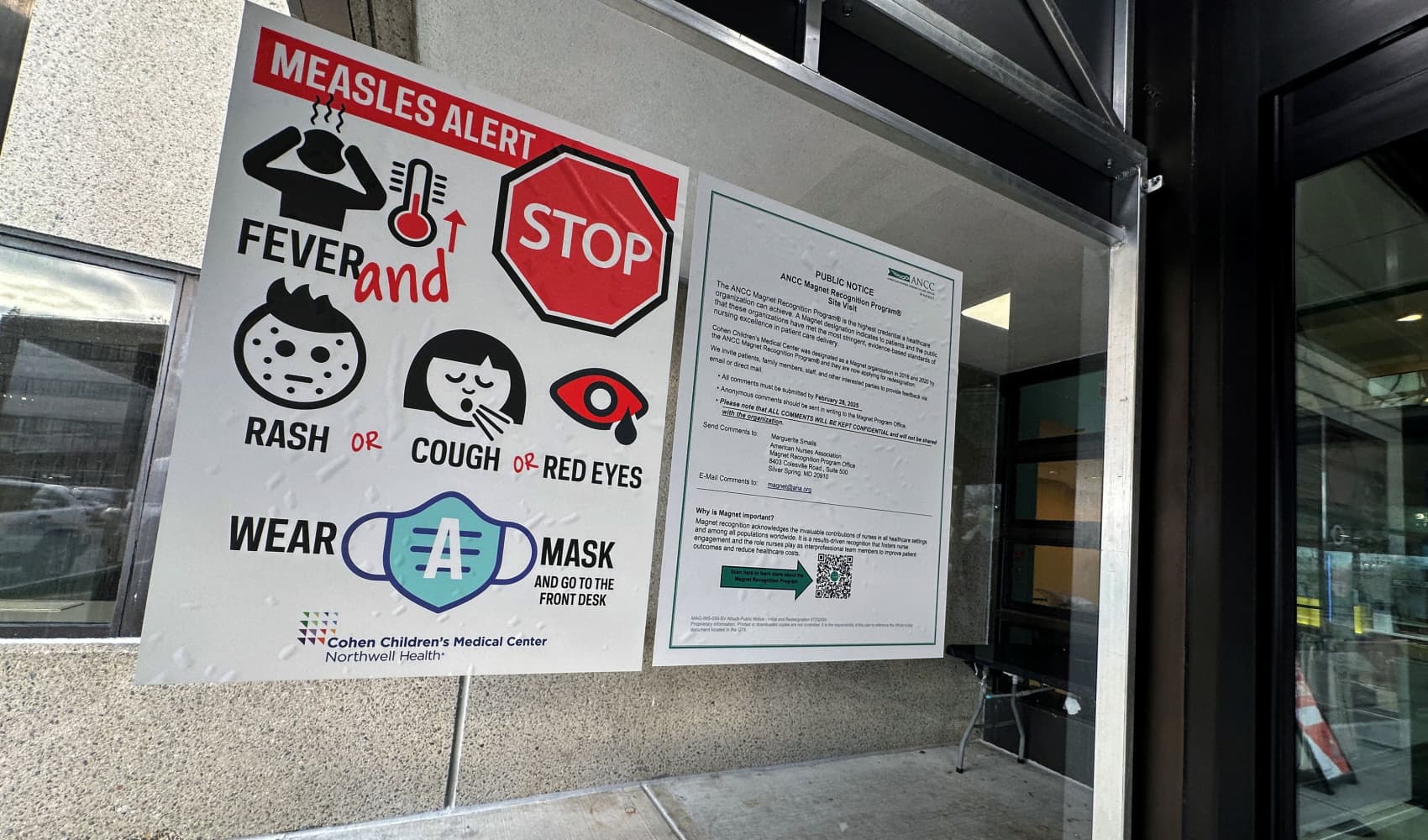

As of Wednesday, there have been over 420 cases of measles this year – already surpassing the total number of cases for 2024. Most are in West Texas, where a growing outbreak has spread into neighboring states, but a handful of cases, linked to international travel, have been reported in other states. The cases have mostly been in unvaccinated people or those with an unknown vaccination status, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Get top local stories in Connecticut delivered to you every morning. Sign up for NBC Connecticut's News Headlines newsletter.

Measles is one of the most contagious viruses in the world, so pockets of under-vaccinated areas can make it easier to gain a foothold and spread, Rader said.

“The worry is that once measles gains a foothold in the community, it’ll transition from isolated outbreaks to an endemic disease,” with consistent presence in the U.S., he said.

‘Sampling bias’

The CDC recommends two doses of MMR vaccine to protect against measles, mumps and rubella, first at ages 12 to 15 months and the second shot at ages 4 to 6 years before entering school. The agency estimates 92.7% of kindergarteners have had two doses of the vaccine.

That’s not high enough, said Dr. Brian Clista, a pediatrician who works in private practice in Pittsburgh.

“The 92% vaccination status reported by the CDC is still below the recommended rate of 95% to produce herd immunity — so it’s not where we need to be,” Clista said.

However, Rader said that the true MMR vaccination rate among young children can be misrepresented by publicly reported numbers, because MMR surveillance is drawn from older children who are already in kindergarten.

Younger children under the age of 5 are not fully captured in surveillance data because they have not reached kindergarten age — although a 2021 estimate from the CDC notes a subset of younger children, namely those who received at least one MMR dose by 24 months, were 90.6% vaccinated for measles.

In Rader’s study, published online in February in the American Journal of Public Health, his team surveyed approximately 20,000 parents of children under 5 from July 2023 through April 2024, finding only 71.8% reported that their children received at least 1 dose of MMR vaccine — much lower than CDC estimates.

More measles coverage:

The researchers used a digital surveillance platform that the CDC has used to estimate things like at-home Covid testing, he said.

Rader downplayed the difference in numbers between his findings and the CDC data, emphasizing that, while accurate, the CDC data does not provide a complete picture — despite its best intentions.

Dr. Scott Roberts, associate medical director of infection prevention at the Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut, who was not part of the research, called the findings “worrisome.”

“This was likely exacerbated by the Covid pandemic, especially because, as Rader notes, many kids catch up on the childhood vaccine schedule when they enter elementary school and the school requires it,” Roberts said.

He agreed with the findings that the true rate is lower than what the CDC reports, likely due to a “sampling bias.”

“With greater homeschooling and greater schooling absences, as occurred during Covid, the more likely there will be more of these kids who do not get the chance to catch up on the childhood vaccines,” Roberts said.

Clista noted that the study has limitations, as the research relied on parents self-reporting information compared to more objective data that the CDC gathers from kindergarten entry forms.

Rader acknowledged that not every child younger than 5 is eligible for the measles vaccine, and his study didn’t specify the exact ages of the children younger than 5 who were unvaccinated.

The pandemic exacerbated vaccine hesitancy

The pandemic disrupted health care access, which made it harder for people to get routine care and increased vaccine hesitancy over the Covid vaccine, which also spilled over and affected MMR vaccine rates, Rader said.

The study found 20% more children were vaccinated for measles when their parents were vaccinated for Covid.

“Unfortunately, routine vaccination is trending substantially lower, although there is the hope that it will catch up,” Rader said.

Katherine Wells, director of public health for Lubbock — the largest city in West Texas, where the current outbreak is centered — said school enrollment requirements should help many children catch up as they enter pre-K or kindergarten.

“However, in Texas, we’re seeing a growing number of parents opting out of vaccinations — a troubling trend that puts communities at greater risk,” she said.

‘We’re headed in that direction’

Measles has been “eliminated” in the U.S. since 2000 — meaning that the country hasn’t had a chain of transmission extend for more than 52 weeks.

“With the absence of sustained measles virus transmission for 12 consecutive months in the presence of a well-performing surveillance system, the United States has maintained measles elimination status since 2000,” a CDC spokesperson told NBC News.

“This temporal boundary, however, was nearly breached in 2019,” said Dr. Jonathan Temte, professor of family medicine and community health at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health. Temte was part of the team that declared measles eliminated in 2000

When he served on a panel to recertify measles elimination in 2011-12, one of his greatest concerns, he said, was the rising rates of vaccine exemptions among children and the cases brought into the U.S. after international travel that could lead to endemic transmission.

Now additional factors might be creating a perfect storm for the U.S. to lose its elimination status, including declining vaccination rates, increasing pockets of unvaccinated individuals and greater ease in travel.

Measles is also contagious before its characteristic rash appears, often creating a delay in diagnosis and allowing it to spread before people know they are infected.

Combining this with the level of complacency toward the public health response and the lack of recognition that an illness from measles can be serious, Temte said, “I would guess that the likelihood of re-establishment of measles in the United States is greater than 50%.”

Other experts are also concerned.

“I believe we’re headed in that direction,” Wells said. “I can’t say for certain whether this will be the outbreak that causes it, but if we don’t take steps to increase vaccination rates nationwide, we will lose our measles elimination status.”

Dr. Michael Mina, vaccine expert and epidemiologist, whose research was the first to discover that measles can wipe out the immune system’s memory of previous illnesses, said he expected cases to continue almost exclusively among the unvaccinated.

“While we do have very many unvaccinated children, whether the virus burns through most of the susceptible or is slower and drives some level of endemicity is tough to say,” he said.

“My concern is the ‘bubbles’ of the unvaccinated are larger and larger and more plentiful and so they start to merge with each other, meaning that a case in one could ignite nationwide cases.”

A similar scenario occurred in Europe about 10 years ago and led to tens of thousands of cases, he said.

“That is a likely scenario for the U.S.,” Mina said. “Whether it’s this year, or next or the following, is tough to say.”

This story first appeared on NBCNews.com. More from NBC News: